A Boy and His Car

This is part 2 in the series, The Decade Long Stephen King Cinematic Orgy. Part 1, with an introduction is here. Spoilers ahead.

In 1983, the release of the feature film version of Stephen King's novel Christine marked the midway point of the Decade Long Cinematic Orgy. The seventh film in seven years, "Christine" is one of four Stephen King films from the Decade that was directed by a legitimate auteur. At the helm here, John Carpenter was coming off a run of three cult classics in "The Fog," "Escape From New York," and "The Thing."

For many reasons, "Christine" was an odd choice, both for Carpenter and as a King adaptation. The novel, which is one of the few that I haven't read, was King's eighth and was actually published the same year that the film appeared. The essential plot, which I'll expand on in a bit, goes like this: Arnie is a nerd who's decided he wants to learn about cars. He "meets" and falls in love with a dilapidated red Plymouth Fury named Christine. Despite some warnings about folks who died in and around the car, Arnie purchases it on the cheap and fixes it up. He becomes obsessed and descends into a mess of psycho-sexual complications involving his family, friends, and love interest. There are many deaths and some tears and at the end, Arnie is dead and Christine is cubed at the dump. Mixed in with all that is some excellent filmmaking, some awkward plot points, and a whole lot of the things that make Stephen King films worth watching even when they fail.

Carpenter opens the film with a brilliantly shot sequence where we see Christine coming off the production line. Christine is the only red Fury in a line of all white Furies. Red clearly distinguishes the car from the rest, but also marks it as a sexual or lustful object. We could even carry this a step further from lustful to sinful or even evil. I read up on the novel on Wikipedia, and it seems as though this scene was entirely new, which is interesting because it serves to completely change the nature of the "monster" in the film. More on that later, though.

In the shot above, we can see one of the first attempts by Carpenter to anthropomorphize Christine. Throughout the film, there are many shots where Christine is framed as a human character, or specific parts of the car are matched with human parts. Here, Christine sizes up one of the workers in a shot that implies her rearview mirror is an eye. In the next sequence, when this same man is looking at the car's engine, Christine slams the hood down on his hand, effectively biting him. A scene later, another worker sits down in Christine to smoke a cigar, only to be found dead in the car's front seat. This takes us into the main action of the film.

From that opening scene, we jump forward 21 years to meet Arnie and his best friend Dennis. Carpenter gives us one long conversation between the two while they drive to school that establishes their relationship. It's the beginning of the school year, and Arnie has decided to take up shop. He wants to learn to work with his hands, and he seems in love with the idea of taking care of a car. It becomes obvious very quickly, why that is: he's a failure with the ladies.

"Gotta get you laid." Dennis says to Arnie, by way of explaining everything that's wrong in his friend's life. Instead of play along, Arnie responds, "I think I'll just beat off." This back and forth, aside from being hilariously uncomfortable, is pure King. Our protagonist is a sexually stunted or immature young man; he may as well be a nuclear warhead for all the destruction he could sew in King's mind.

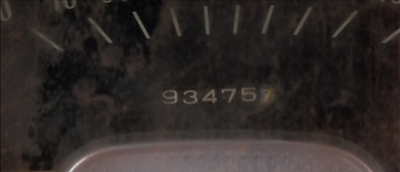

It's not long before Arnie's sexual need is filled by Christine. Dennis and Arnie first encounter the car parked in the overgrown yard of the brother of Christine's former owner. The car looks to be destroyed, but starts up for Arnie right away. His infatuation is total and immediate. Dennis is sure to point out to Arnie that the car has over 90,000 miles on it, but Arnie buys it anyway.

The shot above comes at a pivotal moment of the film, one that brings act 1 to a close. By this point, Arnie has repaired Christine fully. With the repairs completed, Arnie becomes a different person: confident, cocky, and masculine. He asks out the school's new girl, who Dennis had lusted after briefly, and they quickly become an item.

This shot, where Arnie and Leigh kiss while sitting on Christine's hood, is actually a POV from Dennis's perspective. The setting is Dennis's football game. As a play is about to begin, Dennis sees Christine roll into the parking lot. He runs a pass route out of the backfield, only to be distracted by Arnie and Leigh kissing. He does make the catch, but is hit so hard in the process that he needs to be carted off the field. On the stretcher, Dennis looks over again at his friend who has not moved but now watches the medics work.

Here Carpenter clearly intends to stir ambiguity in the viewer about Dennis's attention. Was he transfixed by Christine? Or was it by Leigh, who had earlier spurned him? Or was his attention grabbed by his friend, whose sexual experience he'd previously tried to taken ownership of? Christine has turned the formerly inept and "safe" friend Arnie into a sexual rival for Dennis, and the film implies that he is the first victim of the car's influence.

Arnie's change becomes more pronounced as the film progresses. Here we see the new Arnie during a visit to Dennis's hospital bed. Their roles from the beginning of the film—helpless, lonely masturbator and suave, sexually confident dude—have reversed completely by this point. Dennis is conflicted at this shift in position. On the one hand, he's happy that his friend has seemingly grown, but Arnie does not act happy and has been distant ever since Christine has entered his life.

This type of character arc is again, classic King. Christine has unleashed Arnie's repressed sexual energy, turning him into a badass. But the change is a two sided coin. New-Arnie cannot connect with people in any genial way. He assaults his father at one point, and continually pushes Leigh to the brink of leaving him. It becomes clear that while Christine has unleashed his repressed energy, the car has also become the focus of that energy. We only ever get one truly sexual moment between the young lovers, and it of course takes place in Christine's front seat. Before Arnie can consummate his relationship, Leigh begins to choke on food that she was eating—something we've been told has happened in Christine under her previous owner.

Arnie's transition is complicated by the presence of the film's only real human antagonists: a group of bullies led by a greaser dirtbag character (here named Buddy) who King fans will recognize as a recurring archetype. It's established early on that Arnie is a favorite target of these losers in a scene with very strong homosexual overtones. From that early sequence on, the violence and threats of Buddy and his cronies take on a sexual nature, so it comes as no surprise that once Arnie changes, the bullies feel increasingly threatened and retaliate by smashing Christine, the enabler and center of Arnie's sexual awakening.

Arnie gets revenge for this attack, but only after the film's most overtly sexual encounter between the boy and his car. Encountering his pride and joy utterly destroyed, Arnie flips and finally drives Leigh, who had come to the garage with him, away. He initially sets to work fixing Christine, but soon realizes that the car can repair itself. Arnie steps away, and staring lustily at his machine, says, " Show me." Carpenter originally frames this sequence over Arnie's shoulder, but then moves to tight shots of Christine popping out its dents and setting its parts right. The angles call forth a strip-tease, a show that Christine the sex object puts on for its admirer.

Carpenter never explicitly shows us who is accountable for the deaths of Buddy and his friends. The car mows each of them down, and when the police come around asking questions, Arnie always has an alibi. The implication, and the one that fits most comfortably with the film's narrative, is that Christine has become an extension of Arnie, a manifestation of the sexual energy he could not express before the car came into his life. Any threat against Arnie, or any threat that might separate Arnie from Christine, is neutralized.

This brings us back to the changes between King's book and the film. In Carpenter's film, Christine is shown from creation to be an evil or malevolent vessel. The car was indeed born bad. King's novel leaves this very much open to interpretation. Instead, the car's original owner, Roland, who is never alive during the film, plays a central part in the book's plot. Roland, in both versions, is described as a nasty person; in the film it's implied that Christine may have made him that way, just as it's done to Arnie. King's novel apparently again leaves this question more open, and even implies that Roland's essence inhabits the car and may account for its "behavior."

The end, in either case, is the same. In the above shot we see what becomes of Christine in the final showdown. Dennis and Leigh team up to confront Christine, and in so doing they hope to free Arnie from its spell. Unfortunately, Christine and Arnie are no longer individual entities. Arnie's sexuality now is Christine, and so he and it must destroy the threat that seeks to return him to his humble, nerdy, masturbatory beginnings. Carpenter here creates a visual metaphor for the car's metamorphosis. Christine literally bares its teeth as it prepares to eliminate Leigh and Dennis.

The film's final sequence is almost too heavy handed in its sexual overtones. Leigh has become the bait that Dennis hopes will distract Christine/Arnie long enough so that he can crush the car (Arnie's sexuality) with his bigger (manlier) back-hoe. Just as the threat to Leigh's life becomes the greatest though, Dennis's back-hoe stalls out. He's unable to get it started, and thus can't protect Leigh from Arnie. Despite Dennis's performance issues, Leigh survives, do solely to Arnie's overly aggressive pursuit. When Christine comes crashing through a wall to kill Leigh, Arnie flies through the car's windshield, becoming Christine's final victim.

This only delays the threat, but now with Arnie out of the way, Dennis regains his mojo and eventually uses his over-sized vehicle to destroy Christine. Just as he's putting the car down for good, Carpenter gives us another shot of its odometer. This is the third or fourth time we've seen this same shot (the first is above), and here we notice that the car has returned to zero miles. In drawing energy and attention from Arnie, it has fully regenerated, regaining its potency.

I've focused here almost exclusively on the sexual politics that underlie "Christine," but I should note that I haven't even scratched the surface of what King's story and Carpenter's film contain in this regard. The excellent use of music as a sexual metaphor in the film deserves a full exploration in its own right.

I mentioned at the outset that this was an odd choice, and hopefully by now that is somewhat clearer. "Christine" is a film about sexual awakenings, and like virtually all horror films, about the dangers or threat of sexual repression. What's hard to see past though is that ultimately, this is a movie about a boy and his car. As a novel, this kind of exploration can, and probably does, work. Complex sexual relationships can be explored more thoroughly and intimately in prose; psyches can be probed and subtexts more subtly alluded to. Carpenter has likely created the finest possible version of this story on film, but its just a story that doesn't lend itself that well to the screen.

For the many aspects of the film that do work though, part of me feels that this film may be one of Carpenter's finest achievements. The film truly looks and feels gorgeous. Even still, it's just not a transcendent film like "The Shining," "Carrie," or "Halloween" and "The Thing." With regards to the Decade Long Stephen King Cinematic Orgy however, few of the films so thoroughly incorporate the themes, devices, and subjects that dominate the early and best work of King as does this one. In that regard, "Christine" becomes an important lens through which we can view the rest of the films and work of this time period.